A Reality Apart Starts with a Father with a Travel Bug

My superpower, if I have one, is being able to open my mind to paradigms of reality that other people don't seem to notice. Here's how I think it began.

“We cannot solve our problems with the same thinking we used when we created them.”

-Albert Einstein

I was raised by a father whose values were forged a generation or two before his time. He drilled it into me that there are always at least two sides to any story and that we have a responsibility to fully understand both sides before passing judgment. I’ve since discovered that in the process of considering different sides of an argument something resembling the truth often lies within another paradigm.

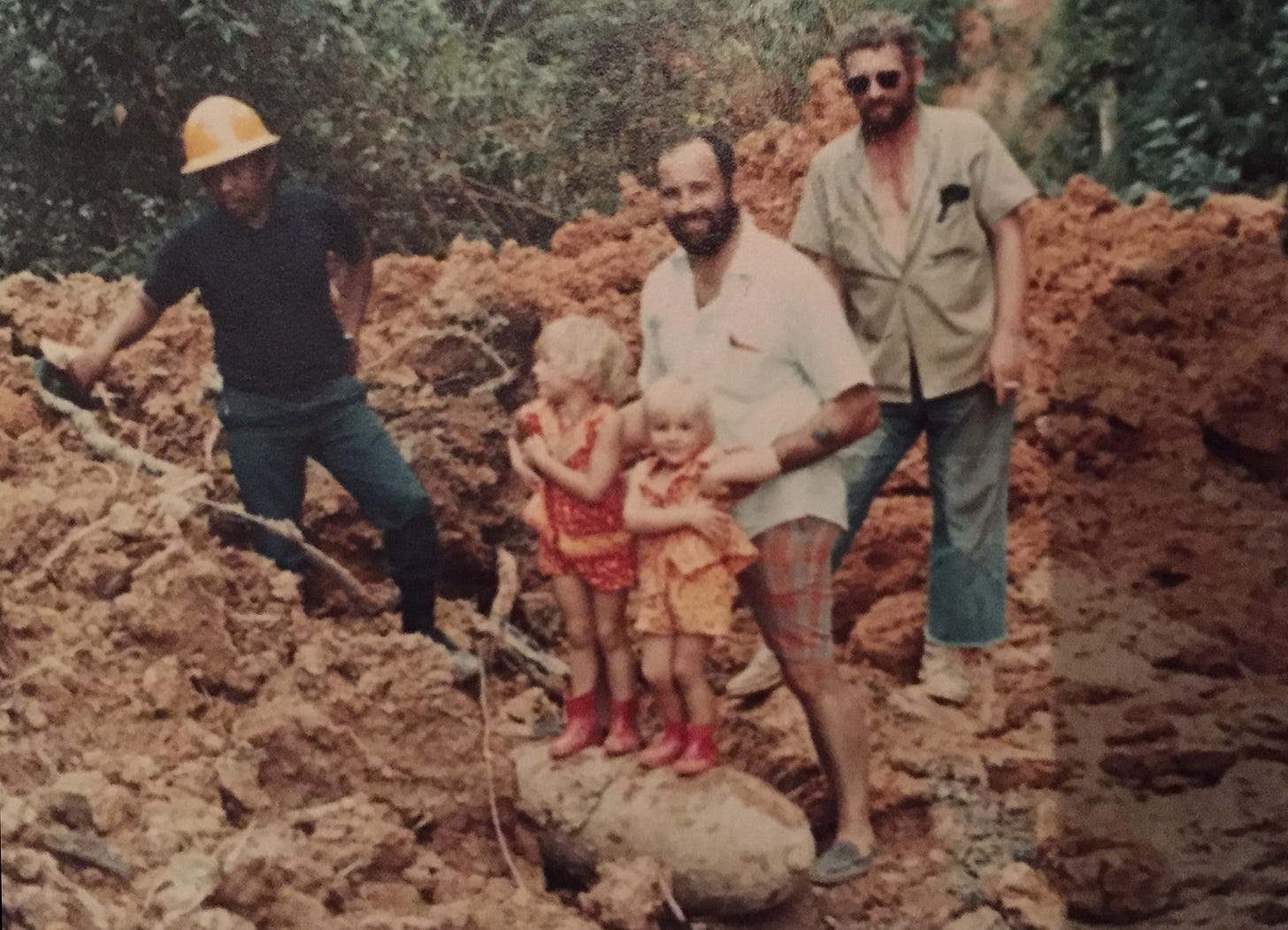

I was three years old when my father took an overseas post and moved me, my sister and mother with him to the jungles of Borneo. Five years later, in the mid-1970’s my dad somehow got a visa to enter the Soviet Union. He obtained tickets for the family to take a three-week trip on the Trans-Siberian Railway as a last hurrah of sorts before we moved back to live in the US. It was an epic journey that began in Japan where we boarded a ferry to Vladivostok, our starting point in the USSR. The trip ended in Helsinki, Finland after a brief stop in Leningrad (St. Petersburg).

The only background my dad gave me before the trip was that the USSR was the largest country in the world. He taught me how to count to ten in Russian and to identify words like restaurant and toilet in the strange Russian script. Along the way I learned things like Lake Baikal was the deepest in the world, and that there was nothing to buy in the shops except for pins featuring the head of Lenin and various landmarks; in the larger cities we found items like Russian dolls and even some amber jewelry. I was disappointed to discover that there was no soda pop or chewing gum available and was bemused by people asking me for my jeans. On the train we mostly ate kasha (cream of wheat) for breakfast and borscht (beet and potato soup) for lunch and dinner. My dad sometimes scored yogurt, dill pickles or pine nuts at the train station markets along the way. I expect vodka was also pretty easy to find.

After five years of trips to colorful and vibrant places like Bangkok, Hong Kong, Singapore, Bali and even to places like Australia and New Zealand, the trip across the Soviet Union didn’t make a huge impression at the time, other than maybe St. Basil’s Cathedral.

It was only a few months later when I stood in front of my 3rd grade class in Massachusetts telling them about my summer vacation that I registered there was something significant to that particular trip. Kids gasped with wide eyes when they realized I’d been to Russia. I was confused. The teacher eventually had to explain to me that the Soviet Union was an enemy of the United States and that they had nuclear weapons. I don’t remember her exact words, but somehow between the other kids’ reactions and the teacher’s explanation I gathered that I’d been to a place of great evil. Only it wasn’t. Sure, the ladies on the train were stout, bossy and largely mirthless. The poverty was evident even to my eight-year-old eyes. Throughout most of the country there was nothing to buy and little to eat of much interest. When we got to the fancy tourist hotel in Moscow I remember my dad enjoying caviar and steak tartare. I had my first taste of cheese wrapped around cherry tomatoes. Delicious! But that didn’t supplant impressions of poor people bent over hoes working in an endless sprawl of potato fields. In the cities people were better dressed but somber and wary -so different from the warm greetings we’d received throughout Asia. Still, no one seemed like an enemy out to kill me - even the soldiers, who were ever-present but unarmed.

I was too young to know about politics but I was old enough to trust in the validity of my lived experience. It acted like a foot in the door between worlds, holding a space for some light to shine through, encouraging a healthy curiosity and a willingness to consider different perspectives, even in the face of overwhelming certainty to the contrary in those around me.

Imagine if every person living in the US in the mid-70’s had traveled across the Soviet Union and experienced the situation there first hand? Imagine if every American had seen the poverty and bleakness and met people cowed by the struggle to get by? There is something useful in the cognitive separation of the leadership of a country from its people. When we can properly envision the mechanisms of power, different options open up in our minds.

Looking back I realize it was quite remarkable that my dad didn’t mention anything about the USSR being Communist. He’d have been as aware of the Soviet threat as anyone. He came of age in the US in the era of McCarthyism, and was a proud Marine who had served during the Korean War. Living and working in Indonesia in the Suharto years, in the aftermath of the murder of millions of supposed Communists, he would have been well versed on the topic. Maybe after a decade of living and working overseas he’d discovered that experiencing the world first hand gave a different impression from the stories in the media back home? Maybe he’d decided that Communists were people too and it wasn’t worth making a big deal about it? I never thought to ask until now, and sadly he’s no longer with us.

After a mere six years living in the Western US, my dad took another job overseas, this time in the remote southern highlands of Tanzania. In the mid-1980’s Tanzania was at the end of President Nyerere’s socialist experiment, beautiful, but economically destitute. It had been largely insulated from Western Influence since it’s independence from colonial rule in 1961. My education in the benefit of keeping an open mind continued in a myriad of ways. I returned to the US twice for a period of a few years each time before resuming a voluntary exile to life abroad, finally settling in northern Tanzania in the early 2000’s for the better part of two decades.

Why “A Reality Apart”?

I returned to the US in 2018 for a year and a half of “normal” life before the pandemic pulled the rug out from under it. As the world around me split into two apparent sides of “the story”, I found myself struggling to make sense of either one. I noticed the media sources I’d relied on 20 years previously for news and perspective no longer conducted interviews between competing views and interests. With time on my hands, and some recommendations from my more contrary friends, I delved into the realm of podcasts that eventually led me to a conversation between Tristan Harris and Daniel Schmactenberger titled “A Problem Well-Stated is Half Solved”. This exploration of the meta-crisis and the breakdown of sense-making resulting from an information landscape shaped by social media algorithms which optimize for time on screen, helped me see the big picture in a new way. The podcast is well worth an hour of your time if you have not yet discovered it. [NB: Both Harris and Schmactenberger have moved on in their warnings about the meta-crisis to focus on what is happening with AI and the evolution of ChatGPT. However, that initial discussion is an excellent framing of the meta-crisis for those new to the subject.]

I’d already become acutely aware of how the systems in the fabric of our economic, social and political lives define our reality and shape how we perceive it. More on that in future posts. Schmactenberger and Harris point out the importance of understanding what systems and technologies are optimizing for and what perverse incentives are built into them. Recognizing this piece was like the image in a 3D picture suddenly taking shape and jumping off the page at me. There are plenty of great minds on Substack and elsewhere articulating this more eloquently than I can. I do, however, have a knack for peering through the cracks in the paradigm and imagining a different reality. What would life be like if we could all conceive of and demand systems that optimize for human capacity instead of for the profit, power and the control of only a few?

I’ve set up this Substack as a way of sharing my observations, stories and inspirations. It will be part memoir and part thought experiment. Most posts will be relatively short. I invite you to join me in the puzzle of envisioning life differently.

Addendum:

When I delved into my dad’s old photos to illustrate this piece, I came across his photos from Moscow with its impressive array of architecture. Somehow the spectacular nature of the buildings did not lodge in my memory as significant. Maybe because I’ve always been more interested in the animate aspects of life than the inanimate? Maybe because the opulence of the building facades didn’t translate to the street-level experience? Here are a few of those photos just for history’s sake.

Great article, enjoyable read. As a fellow nomad I can intimately connect to the experience of living dual realities. looking forward to your future observations/ thoughts.

Let's collaborate?